WARNING [RDA]: Some of the details contained in this article are graphic, can be quite confronting and may cause sadness and distress to some. Reader discretion is advised.

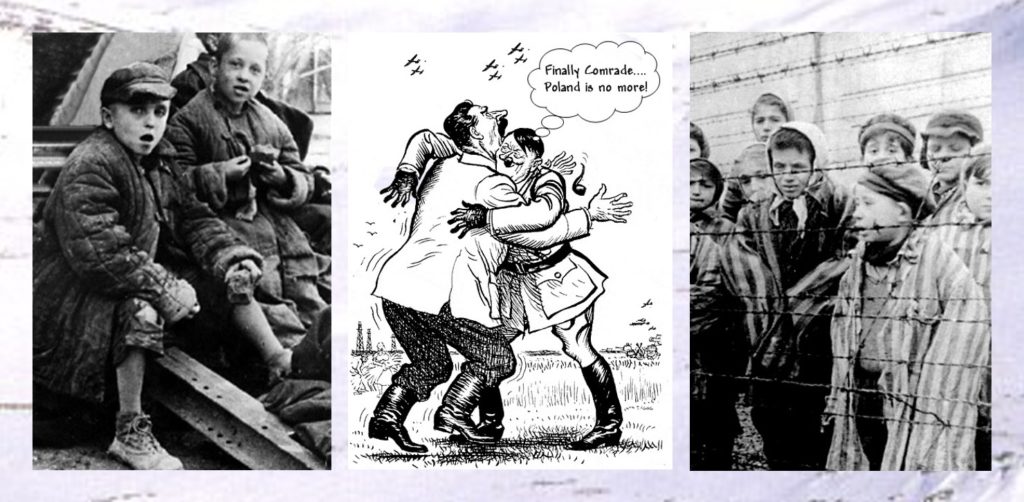

This year 2022 marks the 77th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz on Saturday 27 January 1945, the cessation of the Second World War after Japan’s formal surrender on Sunday 2 September 1945, and the ending of the Holocaust as we know it on Tuesday 8 May 1945; but did you know there were two major genocidal Holocausts of the Poles in the twentieth century: one perpetrated against the Jews by Hitler and his Nazi henchmen and one perpetrated against ethnic Poles by Stalin and his NKVD cohorts?

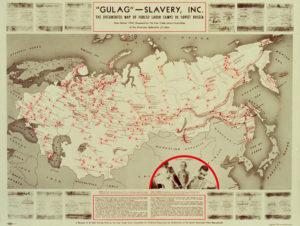

Twenty-twenty-two also marks the 82nd anniversary of the beginning of the systematic deportation and exile of 2,636,000 Polish peoples from the fertile Eastern Borderlands (Kresy Wschodnie) of Poland to the inhospitable wastelands of the Siberian Tundra, Arkhangelsk, Kazakhstan, Kolyma, Uzbekistan and the Russian Arctic (collectively referred to as Siberia by many deported Poles) where they were enslaved, starved, repressed and murdered in ‘special settlement’ forced labour camps (‘Specposiolki’) and Gulags by the communist regime of the Soviet Union.

Those Poles deported, exiled, and who suffered greatly under the yoke of Stalin’s communist utopia – and the hundreds of thousands who never returned – came to be collectively known as ‘Sybiracy’.

The United Nations has still not recognised the event, nor World leaders condemned; there will be no marches, no memorials or other events across the globe remembering this Forgotten Holocaust – the silence of the media will be deafening. Of the unspeakable suffering and loss: No one recalls! No one mourns! No one acknowledges! No one commemorates!

Of this Forgotten Holocaust you will never read about because the Allies were complicit in burying it.

Not one person who ordered, organised, aided and abetted, or condoned the actions of the Soviet terror machine and the actions (and inactions) of the Allies has ever been outed, apprehended, charged, indicted, tried, or convicted of any wrong doing against the Polish peoples.

Now the evening of Friday 9 and Saturday 10 February 1940 was one of the coldest winter nights on record (about -30C); families were woken in the middle of the night and given no more than 15 minutes to pack.

After the formalities of reading the orders of conviction, arrest, forfeiture of property and deportation, the families were evicted from their homes and marched at gunpoint to waiting trains, 50 to 60 men, women and children at a time were herded and crammed into rancid smelling cattle wagons to be transported in their thousands to Siberia.

So began the ‘Forgotten Holocaust’.

Many succumbed to starvation, frostbite, dehydration, mental derangement; some even resorted to eating their own extremities and cannibalism.

Some mothers smothered their babies and infants because there was no food and children were sometimes murdered because they wouldn’t stop crying.

The only view of the outside world many had during the horrific odyssey was through small openings under the roof top, or in the floor which were used for passing out excreta and corpses.

After a most incomprehensible journey lasting for some over two or three weeks, families and communities were often dumped in the middle of nowhere, in the deep snow, with no shelter and wearing inappropriate clothing, no food; they endured unimaginable hardship and suffering.

Their destination was the northern and central regions of the Soviet Union; the area between the Arctic Circle in the north and the Mongolian border in the south: to the Siberian Tundra, Kazakhstan, Arkhangelsk, Kolyma and Uzbekistan – to Siberia!

The rations provided by the selfish and pitiless guards en route were meagre, infrequent and hardly palatable to say the least: black sour bread, often mouldy, dirty, or dry; fish soup (known as ‘Komsa’ or ‘Ukha’) which consisted of salted fish entrails: heads, bones, eyes – but rarely any meat; cabbage soup (known as ‘Shchi’, or ‘Szczi’ which was made from scraps and/or the core of the cabbage) and Russian ‘tea’ (called ‘Kipyatok’) which was made from boiled water flavoured with just about anything you could get your hands on like grass or general vegetation; but if you were fortunate enough, chicory or tea. Sometimes all the deportees received was just simply hot water.

The consequence of partaking in such putrid banquets was usually diarrhoea and dysentery!

In many cases the wagon doors were not opened until the transports were safely on Soviet territory.

Arriving at the Siberian labour camps and settlements red painted planks adorned with white letters read in Russian Cyrillic: “КТО НЕ РАБОТАЕТ ТОТ НЕ ЕСТ (KTO NIE RABOTAJET TOT NIE KUSZAJET – WHO DOES NOT WORK SHALL NOT EAT).”

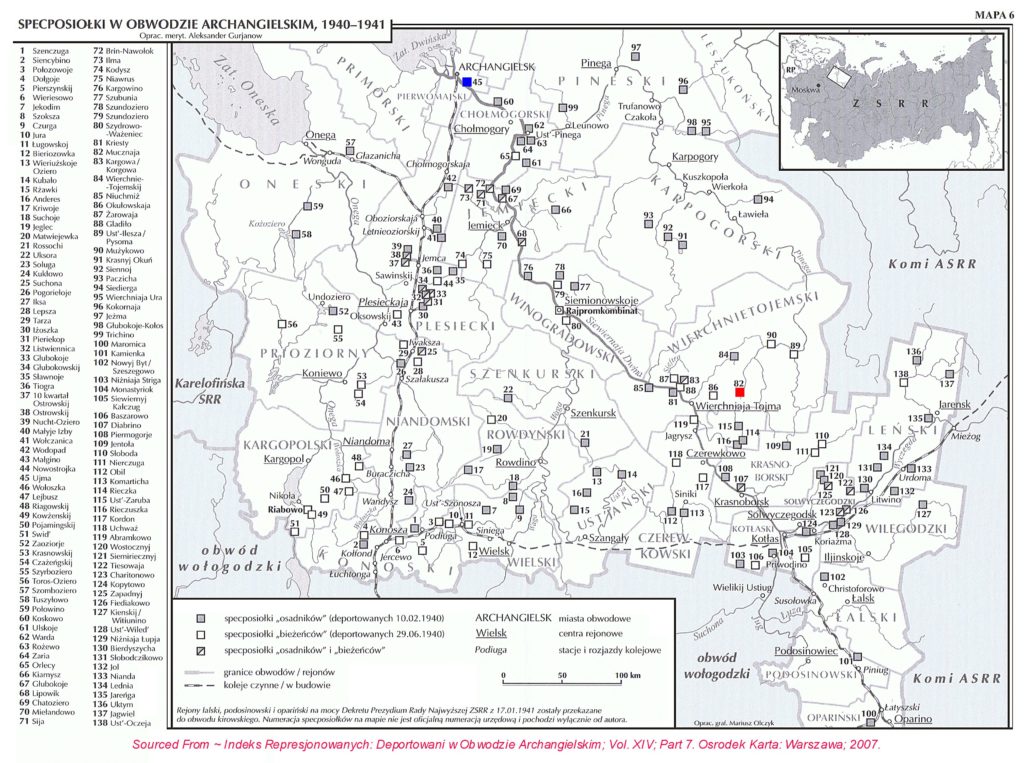

The Poles were told by their captors to forget about Poland, that they would not see their homeland again, Poland was no more and they had to resign themselves to their new lives as Soviet citizens.

But unlike the tender mercies extended to the Jews by the Nazis, there were no such comforts awaiting many of the Poles when they arrived in Siberia. The Poles were thrown meagre tools and told “if you want to survive and live – build!”

Whereas Hitler’s preferred modus operandi for resolving his ‘Jewish question’ was mass murder on an industrial scale using gas and summary executions, Stalin’s M.O. for dealing with his ‘Polish issue’ was to inflict as much suffering as posible upon the Poles so that they would perish slowly, painfully and in a most excruciating way: deportation, starvation, frostbite, dehydration, mental derangement – the elements of nature!

A complete cross-section of Polish society had been deported: government and civic officials, clergymen, academics, military personnel, industrialists, merchants, land owning veterans (soldier settlers) of the Polish-Soviet War of 1919-1921 (‘Osadniks’) and land owning peasants (‘Kulaks’) – they were branded rebels and enemies of the Soviet State and no matter how bad the circumstances they had to adapt, and to survive they had to work; that meant working each day, no matter the weather, even in temperatures as low as -50°C below zero.

Children too were forced to work, to scavenge and forage about in order that their family might survive.

Working twelve to fourteen hours a day with no rest in the week many suffered from malnourishment and exhaustion, and after a very short period succumbed to disease – dysentery, typhoid, malaria and cholera – which ultimately led to their deaths.

Of those eight members of my father’s family (HELON) deported during the evening of Friday 9 and Saturday 10 February 1940 to the ‘special settlement’ in Mucznaja, Arkhangelsk (see Location of the Soviet ‘Special Settlement’ Labour Camps (‘Specposiolki’) map, Camp number 82 boxed in red) only 4 survived. My mother’s (MISIURA) family fared not much better in their deportation to Ujma in Arkhangelsk (see above map, Camp number 45 boxed in blue); only 6 out of 10 members of her family survived.

On Friday 2 August 1940 my great grandmother Karolina Helon died after a short illness brought on by starvation; on Saturday 14 September 1940 her distraught husband Pawel followed her to the grave, and on Tuesday 28 January 1941, my only paternal aunt Jozefa perished from malnourishment and starvation. She had chewed and sucked the end of her fingers off!

Pawel and Karolina were buried in makeshift graves; Jozefa – even in death – was forced to endure more humiliation because the ground was frozen solid when she died and her scantly wrapped body was left for weeks in the doorway before the permafrost melted sufficiently for her to be finally buried, but alas not before the process of decomposition had begun.

But on Sunday 22 June 1941 when Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa and invaded the Soviet Union, the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, made a radio broadcast in which he held out the hand of friendship to the Russians.

Through Churchill, the Polish General Wladyslaw Sikorski initiated negotiations with Stalin for the release of all Poles, which included thousands of soldiers and officers kept in captivity through the vast expanses of the Soviet empire. The Polish-Soviet (Sikorski-Maisky) agreement brokered in London on Wednesday 30 July 1941 – with the blessing of the Allies (Britain and the United States) – only allowed for an ‘Amnesty’.

But the term ‘Amnesty’, applied to the many hundreds of thousands of civilians carried off by the NKVD, was regarded by most Poles as being both insulting and compromising. It begged the question of the deportees’ guilt, since, after all, only those who had been convicted of a crime can be given an ‘Amnesty’. Wherein lay the guilt of the many thousands of mothers and children, the sick and elderly, who had been swept up in the NKVD’s maw?

Of the 2.636 million Poles condemned and sentenced in absentia to an arduous life in exile, only 115,000 (or 4.36%) made it out alive and were officially accounted for! Where are the other 2,521,000 lost souls?

After the ‘Amnesty’, those who made it out of Siberia journeyed through Persia (now Iran) with the remnants of their families to displaced persons’ camps far away in Africa; later to join Anders’ Polish Army under British command to distinguish themselves at Monte Cassino and in other theatres of war fighting for the Allies, for a free Poland!

Stalin’s evil Soviet empire committed this Holocaust with the full knowledge of the Western Allies and the silence, secrecy and concealment surrounding the hardship, suffering, inhumane treatment, torture, murder, execution, and extermination of the Poles still continues to be perpetuated.

Stalin was grateful to the Western Allies for their conspiracy of silence, for preserving his good name. He was even more grateful after the Yalta, or Crimea Conference (Sunday 4 to Sunday 11 February 1945), when the Western Allies granted him the right to enslave all of Eastern, and half of Central Europe under the yoke of communism.

Sold-out and betrayed, the Poles were not even allowed to march in VE (Victory in Europe Day) commemorative parades until their first in London on Sunday 10 July 2005; and that was only after fierce campaigning – and coincidently on the 60th anniversary celebrtating the defeat of Nazi Germany and Japan in World War II.

It is time that the silence, secrecy and concealment surrounding the wanton and inhumane treatment, hardship, suffering and ruthless genocide of the Poles at the hands of Stalin’s sadistic apprentices was acknowledged, remembered, recognized and proclaimed – it happened; we who survive are living testimony to that!

And sadly to this very day there are destitute descendants of those Polish citizens abandoned by the Allies still stranded and helpless in former satellite states of the Soviet Union!

The United States and Britain – supposedly the upholders of democracy and freedom – were then, and are still reluctant to acknowledge that they aided and abetted the Soviet communist regime at the expense of Poland and the freedom of her peoples as promised by the Allies.

It is time that those who were complicit and conspired to commit genocide and ethnic cleansing, those who aided and abetted in crimes against humanity, and those who abused, mistreated and murdered ethnic Poles are brought to account.

This is one of history’s greatest cover-ups! A whitewash for which no one has ever been held responsible or accountable for; a Pandora’s Box of home truths, broken promises, lies, conspiracy and betrayals.

SYBIRACY! The Conundrum of Accounting for the Deported, Victims and Survivors!

As there are no definitive figures to be found from gleaning ‘official’ government, archival, institutional, historical, or scientific sources, determining the actual number of ‘Sybiraks’ deported and exiled to the wastelands of the Siberian Tundra, Arkhangelsk, Kazakhstan, Kolyma, Uzbekistan and the Russian Arctic by the Soviet NKVD between Saturday 10 February 1940 and Sunday 22 June 1941 is always going to be a problematic endeavour, a vehemently provocative matter, a rather contentious subject, and a perpetually debatable issue.

However, utilising the personal testimonies of the survivors and independent witnesses – and by systematically re-examining, re-assessing and re-evaluating extant sources of credible data – a comprehensive, unbiased and accurate conclusion can be reached to quantify the actual number of deportees and survivors.

Albeit some highly regarded and respectable historians, academics and scholars estimate and concede the number of deportees to be between 1.2 and 1.7 million (Piotrowski: 2002; p.11.) their figures are devoid of the actualities, dumbed-down for reasons of political and financial favours and pander to the whims of governments and their sensitivities to known wartime atrocity statistics revealed to them.

Not surprisingly the personal and horrendous testimony of my late father and dozens of other survivors consensually contradicted not only the accepted bureaucratic estimates as to the number of Poles deported to Siberia, but the number of those purported to have survived.

The synopsis of my studies, research, investigations, findings and conclusions were the subject of the article Kresowa Czystka Etniczna (Purging the Ethnic Borderlands) penned by the late Professor Roman Antoszewski (20 January 1935 – 27 November 2017) who was at the time editor of the Kurioza Naukowe (Scientific Curiosities) Journal which was published online in New Zealand (Antoszewski: 2005).

In re-visiting the conundrum I corresponded with a number of Sybiraks from all parts of the world; those people who were actually part of history as it was being made, living witnesses to the historical and tumultuous events they were swept up in.

Aged or not, these observers, eyewitnesses and survivors were not only articulate in recounting their personal experiences, but steadfast in their observations and testimony:

M.O. (United States of America) – “Fifty to a wagon was often reported. I know for a fact that the train carrying my family was packed 50+.”

T.P. (United Kingdom) – “My uncle and mum confirm 65 people to a wagon.”

E.G. (Sweden) – “My mother said that there were 72 people in her wagon.”

Z.H. (Australia, my father) – “There were over 60 of us in the cattle wagon I was in.”

Of the mass deportations and the journeys of the exiled Poles, Dr Keith Sword, Research Fellow at the University of London’s School of Slavonic Studies and East European Studies wrote: “after the trauma of being ejected from their home, the long train journeys to the east were a further terrifying experience for the deportees. Most were transported in freight wagons, packed with as many as 50 or 60 people to a truck” (Sword: 1994; p.19.).

The “transports, or ‘eszelons’” (Sword: 1994; p.19.) as they were called, were “organised in columns of 65 wagons” (Sword: 1994; p.15.).

Now according to noted author, lecturer and Professor of Sociology in the Social Science Division of the University of New Hampshire, Manchester (USA), Tadeusz Piotrowski, any ‘official’ figures do not take into account “both children and adults (who) froze to death by the thousands on their way to the stations and in the box cars in Poland and all along their long journey to their final destinations” (Piotrowski: 2002; p.16.).

Calculating the Number Deported, the Victims, and Survivors?

“Figures produced by the Ministry of Justice in London in 1949 suggested that around 1 660 000 Polish soldiers and civilians were deported to the USSR” (Allbrook & Cattalini: 1995; p.17.).

“In addition, there were approximately 647,000 POWs, Red Army recruits and concentration-camp victims in the Soviet Union as of June 1941” (Piotrowski: 2002; p.12.); so when coupled with the Ministry of Justices’ accounting for the number of soldiers and civilians deported, the number of deportees swept up in the NKVD’s maw would total 2,307,000 persons.

Now considering the observations, testimony and accounting of observers, eyewitnesses and survivors as previously stated, it is possible to judiciously reckon the average number of people per wagon for the purposes of statistical calculation, analysis and evaluation: (M.O.) 50 + (T.P. ) 65 + (E.G.) 72 + (Z.H.) 60 + (Keith Sword) 55, or 302 ÷ 5, which would equal 60.4 persons per wagon.

Sword (1994; pp.15 & 19.) states each ‘eszelon’ (transport) was made up of a “column of 65 wagons,” therefore if the number of wagons (65) is multiplied (X) by the average number of persons per wagon (60), then it can be reliably concluded there was on average 3900 persons per column being deported from each location.

Another promising approach to the “question of numbers is provided by Polish railway employees who, after all, had firsthand knowledge of the preparations being made for the deportations and who operated the trains bound for the interior of the Soviet Union. According to their reckoning, the occupation authorities utilized from 120 to 150 trains for each of the deportations” (Piotrowski: 2002; p.12.).

Having this vital evidence on hand and relying on additional information, it is estimated that: “110 trains were used in the first deportation (Friday 9/Saturday 10 February 1940), 160 in the second (Friday 12/Saturday 13 April 1940), 120 in the third (Friday 28/Saturday 29 June 1940), and 120 in the deportation of (Friday 13 – Sunday 22) June of 1941” (Piotrowski: 2002; p.12.).

Therefore, based on the fact that the transports were to be “organized in columns of 65 wagons” (Sword: 1994; pp.15 & 19.), and in view of the number of persons occupying them at estimates ranging from “sixty or so” (Sobierajski: 1996; p.25.), to “50 or 60 to a truck” (Sword: 1994; p.19; Allbrook & Cattalini: 1995; p.27.) it would be pragmatic to conclude the total number of persons deported would have been in the vicinity of 1,989,000, or 2,636,000 when coupled with the known “647,000 POWs, Red Army recruits and concentration camp victims in the Soviet Union as of June 1941” (Piotrowski: 2002; p.12.).

Of the 2.636 million Poles condemned and sentenced in absentia to an arduous life in exile, only “about 115,000” (Piotrowski: 2002; p.21.) were evacuated from Soviet territory and officially accounted for by the Allies. Some 2,521,000 ethnic Poles remain unaccounted for.

Doing the Math!

The first deportation of 9/10 February 1940 @ 60 (persons per wagon) X 65 (number of wagons per column) = 3900 persons X 110 transport columns = 429,000 persons deported.

The second deportation of 12/13 April 1940 @ 60 (persons per wagon) X 65 (number of wagons per column) = 3900 persons X 160 transport columns = 624,000 persons deported.

The third deportation of 28/29 June 1940 @ 60 (persons per wagon) X 65 (number of wagons per column) = 3900 persons X 120 transport columns = 468,000 persons deported.

The fourth deportation 13-22 June 1941 @ 60 (persons per wagon) X 65 (number of wagons per column) = 3900 persons X 120 transport columns = 468,000 persons deported.

Therefore, the total number of Sybiraks deported from February 1940 to June 1941 would have numbered in total 2,636,000 persons; being 1,989,000 civilians plus the 647,000 POWs, etc.

Recognition | Remembrance | Repentance | Restitution

It is time the world acknowledged and accepted there were two major genocidal Holocausts of the Poles during World War 2: one perpetrated against the Jews by Hitler and his Nazi henchmen and one perpetrated against ethnic Poles by Stalin and his NKVD cohorts!

It is time that the silence, secrecy and concealment surrounding the wanton and inhumane treatment, hardship, suffering and ruthless genocide of our Polish kin, kith and brethren at the hands of Stalin’s sadistic apprentices was acknowledged, remembered, recognized and proclaimed – it happened! We who survive are living testimony to that.

It is time that those who ordered, orgainised, and were complicit and conspired to commit genocide and ethnic cleansing, those who aided and abetted in crimes against humanity, those who abused, mistreated and murdered ethnic Poles, and those who condoned the very same are brought to account.

References:

Allbrook, Maryon and Cattalini, Helen. The General Langfitt Story: Polish Refugees Recount Their Experiences of Exile, Dispersal and Resettlement. Australian Government Publishing Service: Canberra; 1995.

Antoszewski, Roman. Kresowa Czystka Etniczna (Purging the Ethnic Borderlands). Kurioza Naukowe (Scientific Curiosities). ISSN 1176-7545: Auckland; Vol. 55; No.930; 15 February 2005.

Piotrowski, Tadeusz. Deportation, “Amnesty,” and the Polish Diaspora. The Soviet Ethnic Cleansing Campaign Against the Poles During World War II. Occasional Papers in Polish and Polish American Studies, Number 12. The Polish Studies Program, Central Connecticut State University: New Britain, Connecticut; 2002.

Sobierajski, Telesfor. Red Snow: A Young Pole’s Epic Search for His Family in Stalinist Russia. Leo Cooper: London; 1996.

Sword, Keith. Deportation and Exile: Poles in the Soviet Union, 1939-1948 (Studies in Russia and East Europe). St Martin’s Press Inc. New York; 1994.

Revisions:

Article originally published 2013. Revised: 14 March 2025; 30 November 2023; 16 January 2023; 8 February 2022; 10 January 2022; 7 January 2022; 31 December 2021; 2 December 2021; 4 October 2021; 27 September 2021; 11 February 2021; 10 February 2021; 9 February 2021; 3 February 2021; 1 February 2021; 30 January 2021; 1 February 2020.

My father-in-law and his family were interned by the NKVD in Siberia, he was 9 years old. They all got typhoid, his mother died, father went off with Gen. Anders and the Red Cross took, what they classed as orphans, by road to Persia, then by boat to S. Africa. Father fought across N. Africa and Italy, Monte Cassino). Father and son reunited by the Red Cross after the war in GB.

My father and family suffered this fate, amazingly my father and his two older brothers, safely ended up in Tengeru. Arriving in Canada around 1949. This history is important and needs to be shared. Thank you Mr Helon for keeping my history alive.

My dad (the oldest child) was 8 years old at the time of deportation to Kazakhstan, my aunt was a 4/5 y/old, and my uncle Stanislaw 9 months old when deported in April 1940. After enduring lots of suffering and illnesses, and with the help of other people, they returned to Poland in 1946. My grandmother never believed and acknowledged the fact that the love of her life (whom she missed terribly and prayed for all those years in Kazakhstan to be reunited with), her husband Jozef Libura, a Polish army officer was killed by the NKVD in Charkow. Despite that information coming, she kept searching for him through Red Cross until her passing in 1954. Thank you for this article.

I read this with tears in my eyes. You’ve told my father’s family’s story. They are all gone now but these are the stories I grew up hearing. My grandfather was arrested first and sent to Katyn which he survived. Babcia, Dad and my uncle were arrested and sent to Russia, dumped in the middle of nowhere. Babcia picked potatoes for a farmer all day long and was given one bag of potatoes at night as payment. My grandmother was then sent to a Gulag after she made a comment that if she had dynamite she would blow the Russians up. She was feisty and I remember her as being quick to argue and speak her mind. Dad and uncle Henry were then sent to an orphanage in Siberia. They starved and froze for a year and were beaten if they spoke Polish. When Polish political prisoners were released, the boys were miraculously found by babcia and then they were all found by my grandfather. After some travelling they spent a blissful year in Iran which Dad said was heaven because he could eat all the oranges he wanted. My grandfather then went on to fight at Monte Cassino and was crippled soon after and sent to England. Dad and the others spent 1942-48 in Uganda, which Dad always spoke very fondly of. I have visited there three times since he died in 2013, just after turning 82. The church built by the Polish refugees at Nyabyaya in Masindi district was restored for its 75th anniversary. There is a forestry college where the camp stood. There is still a working water pump and some huts plus the building which was used as a post office. It was extremely emotional walking the grounds where Dad spent his teen years and spoke so fondly of. I received a standing ovation from the local parishioners when I spoke to them of my Dad’s gratitude for the safety they received while there and thanked them. The local people were never even told that the refugees were being taken away. It was assumed that they had returned to Poland and I explained that since Poland was never freed after the war due to the Russians staying and these people knew very well that they could not trust Russian powers, they migrated to other countries. The family was reunited in England in 1948 and then my immediate family migrated to Australia in 1973. When I spoke about Dad’s life at his eulogy, I was told that a movie should be made about his childhood years. I know many people here can well relate with your own similar stories.

My mother’s journey was identical! Ended up in UK in 1948 and never saw Poland, or her family there again.

Yes, I too remember all the horrible sufferings of my family, mother and grandmother in Siberia during World War II. My mother was a young woman then. Transported in filthy wagons; no questions asked when the toilet stop will be. I was told many scary situations by grandma of how her legs or feet bled because they walked long distances ending in Persia (Iran). Hungry and exhausted, grandma sold her wedding ring to buy a pillow off someone because her child (my mother) became very ill with typhus fever. Grandma’s husband, an officer in the Polish Army, died somewhere in the snows and his body was never found. Anyway they were transported to Tengeru in East Africa. Eight years later in 1950 they went to Donnelly River Mill (bush country) West Australia. I was born in Africa in 1944. My memories of kindergarten and playing by our round straw roof hut. I would dearly love to write a book as there is so much more to say like how we were given food by the English Army based there; oh how I still love corn and boiled eggs and bread with sugar sprinkled on top. This cannot be forgotten! One day I hope someone will make a professional movie about all the peoples’ experiences, good and bad – maybe call it “Under the African Sun?” My mother died at 60 in Adelaide, South Australia, a stroke and paralysed for over 3 years at home. My grandmother outlived three husbands, lost two children to convulsions in Poland before the War, then her last daughter (my mother) in Adelaide. Grandma died at 93 years of age. I married a teacher, have a son and a daughter, and my main interest for the last 48 years is as a practising Visual Artist mainly exhibiting with the Royal South Australian Society Of Arts in Adelaide and organizing Art Exhibitions for the Polish Dozynki Festivals in South Australia for going on 30 years now!

Sadly, my father’s (Slawomir (Stanley) ZAREWICZ) only memory of this is standing on a train platform with an older woman and young girl. We have no idea what happened to his family. My father was born in 1936. Ended up in refugee camp in Leon , Mexico and eventually Pittsburgh!

This all makes very powerful and disturbing reading. My Dad, Uncle and Babcia were on that February transport. They were sent to Yuznejj in the Taiga. My Babcia is buried in Doulhab cemetery in Teheran. Dad was sent to Iraq and the Polish Airforce. He arrived in Glasgow, Scotland on 30 May 1942. My Uncle stayed with General Anders and was with the 3rd Carpathian Rifle Brigade and won the Medal of Valour at Monte Cassino. Dad spoke very little of his experiences because he just couldn’t relive those memories. How can we make Governments take responsibility for past failures, and get this fully into the public domain? How can we change school history lessons to include the true scale of Stalin’s Ethnic Cleansing against the Polish nation, and all the other peoples who were murdered, or worked to death in these Siberian hellholes? I’ve tried many times writing to national newspapers about this forgotten holocaust but my letters are never published or investigated.

I live in Glasgow now; my aunt was sent to Siberia. Please don’t give up writing about your family history. There must be someone out there who will publish your book, please keep writing. The world needs to know what happened to the Polish people sent to Seberia. They lived and survived and you are the one to tell their story. You are the voice for your family who have passed away. I definitely would buy your book.

I am British but my neighbour was born in Tehran to Polish parents in 1945. We live in Hampshire, and last year on the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which made her incredibly angry and upset, she lent me a book written by members of the Siberian Society of the USA, of memories of what happened in eastern Poland on the night of 10 February 1940, and after that, which led her parents to Tehran and ultimately London. My neighbour’s sister, who was about 15 years older than my neighbour, had written one of the chapters.

I had a Polish-Canadian schoolfriend growing up in the ’70s, so I’d always been interested in Poland and was aware of what they did in the war, RAF etc, but nothing prepared me for what I read in the book. It stayed with me and always will.

My neighbour’s parents and children were, like everyone else, deported east into Soviet Russia where they were put to work in a factory, with tiny pay to buy a little food. They heard that they were “free” in 1941. Obviously they were destitute, with no clothes or food, but they somehow walked their way south thousands of miles to Kazakhstan. My neighbour’s father joined the Army there; the Army fed them all and the family were put on a ship to cross the Caspian Sea to Iran, which was under British control by then.

My neighbour’s mother was pregnant with her, and she gave birth in Tehran. Then it seems people went by sea via Karachi all over the globe – to East Africa, across via Australia and the Pacific to Mexico, with some ending up in Chicago where there was an existing Polish population. Others including my neighbour’s family went to Beirut, Lebanon, which my neighbour’s sister loved (she was about 17-18 by then). She and at least one brother ultimately emigrated to Chicago from London, but my neighbour and her parents stayed in London. Now she is in her 70s, married to an Englishman, had 3 girls and has grandchildren. But the trauma passed down through her parents is evident.

I will never forget what she told me and what I read in her sister’s book.