Helon Families Deported and Exiled to Siberia!

Arrest, Deportation and Banishment!

“On the night of Friday 9 February 1940 my grandparents Pawel and Karolina Helon (nee Mulka), who lived in the village of Pawlow with my uncle Stefan, were visiting my parents’ farm in Krzywe.

“My grandparents were supposed to go back to Pawlow later that day so that my family could visit my grandad Jozef Zielinski in Budki on Saturday.

“However, because the snow was really deep and soft, the trip to Budki was put off and my parents Michal and Genowefa Helon (nee Zielinska) insisted that my grandparents and uncle stay the night with us.

“We all ate a hearty meal and went to bed early that evening because it was very cold, everything seemed normal; there was no hint of anything untoward.

“It was sometime in the early hours of the morning of Saturday 10 February 1940 that everyone was awoken by really loud and continuous banging on the front door as well as the feverish yelling of a Russian soldier: ‘otwieraj (open the door)!’

“My father opened the door at which time three men forced their way in; one a Russian soldier pushed a long rifle fitted with a bayonet menacingly towards my father’s face and yelled – ‘siadać (you sit)!’

“Of the others, one was a Ukrainian in the local NKVD militia, the other – who had a scarf covering his face – turned out to be the local Jewish (2) shopkeeper.

“As the Russian soldier proddingly gestured with his rifle, he shouted to my mother: ‘zabieraj dziechi, i zbieraj się (get the children and get out)!’

“But my mother, so resolute, stood firm and continued to dress me and my sister Lodzia (born Jozefa Leokadia), all the time pleading to be able to get some bread from the pantry.

“The Russian soldier screamed to her, ‘only a little bit, and a bit of meat is all you are allowed to take.’

“As my mother was coming from the pantry, she noticed that the man who was previously unknown to her was desperately trying to hold his scarf up across his face.

“My mother immediately recognised him: ‘Szmojko (3) – why are you doing this; where are you taking us?’

“As the Russian soldier was prodding threateningly and gesturing everyone on, the Jewish shopkeeper yelled to my mother, ‘you never had credit in my shop because you always had to pay in cash – now you will have neither where you are going!’

“All the time while my grandparents were trying to dress (they were in their 60s) – my uncle readied them as best as he could – the Russian soldier continually signalled with his rifle for them to move quicker, yelling at then: ‘Szybko! Szybko! (Hurry up! Hurry up!)’

“Through all this, the militiaman was ransacking the house, turning everything upside-down, throwing things everywhere and breaking whatever he could; demanding ‘dokumenty, dokumenty (documents, documents)!’

“When we all got outside there was a sleigh ready to take us away: why, where, what for – we had no idea; at the front was a previously employed Ukrainian farmhand with a smug look on his face.” (1)

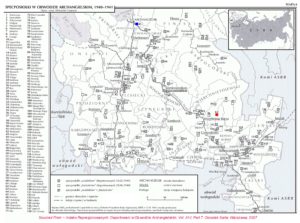

“My mother had barely 15 minutes to ready my sister and me and to pack a few essential things” (1) for the long “four week journey to the Soviet ‘Special Settlement’, Labour Camp Specposiolki #82, Mucznaja (7; p. 77.) in the Wierchnie-Tojomskim Region, Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia – about 340km to the south-east of Arkhangelsk.” (4)

“In the dead of night we were taken to the railway station at Radziechow” (1) like hundreds of others where, with us, there were already gathered “1420 persons” (7; p. 68.); and there, amidst all the chaos and confusion, we waited.

“All that we had were the clothes on our backs and a few sacks with some bread, meat and items of clothing. But I guess we were lucky though, because so many had nothing.

“What could not be confiscated or stolen, was burnt!” (1)

On this one night alone, 429,000 unwary Poles were deported from the eastern territory of Poland (known as the ‘Kresy’ Region) to the wastelands of the Soviet Union and the vast tundra that lay beyond.

More deportations would follow: 12/13 April 1940 at 624,000 persons; 28/29 June 1940 at 468,000 persons, and 13-22 June 1941 at 468,000 persons.

Coupled with the known 647,000, POWs, forced Red Army recruits and concentration camp victims in the Soviet Union as of June 1941, in all 2,636,000 persons were deported and exiled.

“Of the total number of Poles deported to the Soviet Union and beyond, only 115,000 (or 4.36%) made it out” (5) of the Soviet Union through Pahlevi, Persia (Iran) with the remnants of their families to join General Wladyslaw Anders’ Polish Army under British Command.

So Why was the Family Arrested?

Well, “Pawel Helon was known to have been a devout Polish Patriot who had supposedly taken part in uprisings in Poland proper (Izdebki, district Brzozow) in the latter years of the 19th century.” (6) Fleeing east to Pawlow in Austrian Galicia to escape arrest, Pawel was appointed a Royal Courtier in the service of Count Stanislaw Badeni, Marshal of the Galician Diet.

According to testimonial evidence “Pawel was an ‘Osadnik’, i.e. one given land in exchange for military service.” (4) Osadniks were vehemently hated by the Bolsheviks since the Polish-Soviet War of 1919-1921.

TROIKA: Conviction Without Trial!

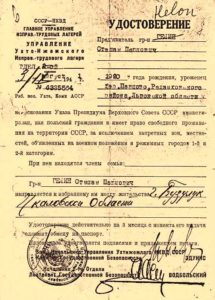

Before their deportation – and in secret many months beforehand – my great grandfather Pawel, his wife Karolina, sons Stefan, Michal and his wife Genowefa and their children Zbigniew and Jozefa Leokadia were convicted and sentenced by a local NKVD (or Special) Troika of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (Narodnyy Komissariat Vnutrennikh Del – the dreaded NKVD).

A Troika is an administrative or ruling body of three; it usually meets in secret to decide the fate of accused persons without any public or fair trial, legal aid or representation.

The members of the Troika are effectively judges, jurors, and executioners.

Although local NKVD Troikas had judicial rights, they had no authority to order death sentences.

HELON, Genowefa (GELEN, Genovefa Iosifovna); daughter of Jozef; born 1912, Lviv province, Radekhov district; Pole of lower education; lived Lviv region, Radekhov district; sentenced to deportation, special settlement Mucznaja in the Arkhangelsk region, arriving 10 March 1940, Verkhnaya-Toyma district; released from special settlement under amnesty 2 September 1941, declared destination Astrakan, Stalingrad Oblast. (7; p. 304.)

HELON, Jozefa Leokadia (GELEN, Yuzefa Mikhailovna); daughter of Michal; born 1938, Lviv province, Radekhov district; lived Lviv region, Radekhov district; sentenced to deportation, special settlement Mucznaja in the Arkhangelsk region, arriving 10 March 1940, Verkhnaya-Toyma district; died 28 January 1941. (7; p. 305.)

HELON, Karolina (GELEN, Korolina Pavlovna); daughter of Pawel; born 1882, Lviv province, Radekhov district; Pole of lower education; lived Lviv region, Radekhov district; sentenced to deportation, special settlement Mucznaja in the Arkhangelsk region, arriving 10 March 1940, Verkhnaya-Toyma district; died 2 August 1940. (7; p. 305.)

HELON, Michal (GELEN, Mikhail Pavlovich); son of Pawel; born 1913, Lviv province, Radekhov district; Pole of lower education; lived Lviv region, Radekhov district; sentenced to deportation, special settlement Mucznaja in the Arkhangelsk region, arriving 10 March 1940, Verkhnaya-Toyma district; released from special settlement under amnesty 2 September 1941, declared destination Astrakan, Stalingrad Oblast. (7; p. 305.)

HELON, Pawel (GELEN, Pavel Voitsekhovich); son of Wojciech; born 1872, Lviv province, Radekhov district; Pole of lower education; lived Lviv region, Radekhov district; sentenced to deportation, special settlement Mucznaja in the Arkhangelsk region, arriving 10 March 1940, Verkhnaya-Toyma district; died 14 September 1940. (7; p. 305.)

Additional note included in the Indeks Represjonowanych that Pawel Helon was released from special settlement under amnesty 2 September 1941 and declared his destination to be Astrakan in the Stalingrad Oblast. (7; p. 305.)

HELON, Stefan (GELEN Stefan Pavlovich); son of Pawel; born 1920, Lviv province, Radekhov district; Pole of lower education; lived Lviv region, Radekhov district; sentenced to deportation, special settlement Mucznaja in the Arkhangelsk region, arriving 10 March 1940, Verkhnaya-Toyma district; convicted and sentenced by local NKVD (or Special) Troika of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (Narodnyy Komissariat Vnutrennikh Del) in July 1940 for sabotage. (7; p. 305.)

HELON, Zbigniew (GELEN, Zbignev Mikhailovich); son of Michal; born 1920, Lviv province, Radekhov district; lived Lviv region, Radekhov district; sentenced to deportation, special settlement Mucznaja in the Arkhangelsk region, arriving 10 March 1940, Verkhnaya-Toyma district; released from special settlement under amnesty 2 September 1941, declared destination Astrakan, Stalingrad Oblast. (7; p. 305.)

Exile to Siberia!

The crude transports were already stationed at holding yards in Radziechow on Monday 5 February 1940; being outwardly simple cattle rail cars, no one gave a second thought as to the insidious designs of the occupying Soviet Authorities – their ruthless intentions that would be brutally realized only a few days later.

“Saturday 10 February 1940 was one of the coldest Winter days on record; in the early hours of the morning, with temperatures as low as -30°C,” (8) entire families were unexpectedly and abruptly awoken throughout the ‘Kresy’ and given no more than 15 minutes on average to ready themselves for the uncertain fate that awaited them.

Those who tried to resist were savagely beaten senseless, those that tried to run were shot without compunction in the back without warning!

“The family Helon: Pawel, his wife Karolina, their youngest son Stefan, oldest son Michal, his wife Genowefa (nee Zielinska) and their 2 children, son Zbigniew and his sister Jozefa Leokadia” (4) – horribly uncertain of the fate that awaited them – were herded into a cattle rail car to face the most horrific, arduous and terrifying journey of their lives.

“Under command of the belligerent NKVD Commissar Sokolow of the Soviet Red Army’s notorious 227th Regiment, 13th NKVD Escort Troops Division (Headquartered in Kiev), 1420 bewildered and terrified souls embarked on a perilous four week journey of almost 2,400 kilometres to oblivion.” (7; p. 68.)

My mother’s family Misiura: Zachariasz, his wife Helena, sons Boleslaw, Maksymillian, Jan, Antoni and daughters Helena, Elzbieta (and Maria later born in Exile) were deported from their farm at Osada Wojskowe (Military Settlement) Rejmontowka – originally and subsequently known as Wolka Lubieszowska – west of Lubieszow, Wolyn, Poland (now Lubieszow, Wolyn, Ukraine), “to the Soviet ‘Special Settlement’ Labour Camp Specposiolki #45, Ujma (7; p. 73.) in the Pierwomajski Region, Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia.” (9)

In command of the Deportation Transports – stationed at holding yards in Kamien-Koszyrski since Thursday 1 February 1940 – was the “NKVD Commissar Popow of the 147th Battalion, 11th Brigade, NKVD Railroad Security Division. In total there would be 1672 Polish compatriots ignominiously shipped liked cattle” (7; p. 68.) almost 1700 kilometres, traversed over 3-and-a-half-weeks, in unsanitary conditions, exposed to the elements, forced to endure hunger, starvation, disease and death all around; many died enroute, some – men, women, and children – were lucklessly, and heartlessly abandoned when trying to bury their loved ones when the trains stopped for fuel.

“When we finally arrived at who knows where, all we could see rising from the snow was a wooden tower to one side of a barbed-wire entrance which had an ominous painted sign on a large red painted plank above it.” (1)

“The sign read in Russian Cyrillic: КТО НЕ РАБОТАЕТ ТОТ НЕ ЕСТ (KTO NIE RABOTAJET TOT NIE KUSZAJET – WHO DOES NOT WORK SHALL NOT EAT).” (1)

But unlike the tender mercies extended to the Jews by the Nazis, there were no such comforts awaiting the Poles when they arrived in Siberia.

“For a few Roubles my parents, grandparents and uncle worked exhaustingly for 16 or so hours every day felling trees.

“My sister and I were always dirty, our clothes were rags; we were cold, we were starving, we had to gather branches and off-cuts.” (1)

Conditions were so terrible that the children were sent scavenging by their parents or guardians for any scraps that could be gleaned from the leftovers accidently tossed away by their captors. “There were often fights among the starving children over such things as a blade of grass which was held in high regard like a nugget of gold!” (1) The mortality rate among children and the elderly was extremely high.

“What little possessions people managed to keep hidden from the dreaded NKVD soldiers and their sympathizers were soon bartered for any meagre rations of food and essential supplies.” (1)

On Friday 2 August 1940 my great grandmother Karolina Helon died after a long illness brought on by starvation; on Saturday 14 September 1940 her distraught husband Pawel followed her to the grave, and on Tuesday 28 January 1941, my only paternal aunt Jozefa perished (9) from malnourishment. She had chewed and sucked the end of her fingers off!

Pawel and Karolina were buried in makeshift graves, Jozefa – even in death – was forced to endure more humiliation “because the ground was frozen solid when she died and her scantly wrapped body was left for weeks in the doorway before the permafrost melted sufficiently for her to be finally buried, but alas not before the process of decomposition had begun.” (1)

The Flight to Freedom!

After the Sikorski-Maisky Agreement was signed in London on Wednesday 30 July 1941 by the prime minister of Poland, Władysław Sikorski and the Soviet ambassador to the United Kingdom Ivan Mayski, information began to filter through to the various Camps that there was an ‘Amnesty’.

Zbigniew Helon, his father Michal and mother Genowefa left Mucznaja, via Kotlas, on Tuesday 2 September 1941 on a log raft heading south along the River Jagrysz “bound for the city of Astrakhan in Stalingrad Oblast” (9) – situated 100 kilometres from the Caspian Sea – where a Free Polish Army was being raised. But it was not all plain sailing once the Soviets realized they were letting their captive workforce (‘slaves’) go, so they organized squads of NKVD Militiamen to hide along the riverbanks and shoot the fleeing Poles. Their primary targets being the children at one end of the scale, and head male at the other; their reasoning: kill the child the parents will try to save them, or kill the head male and the others will surely perish.

“My uncle Stefan had disappeared sometime before we left the camp; his whereabouts were unknown.” (1)

Zachariasz Misiura and the surviving members of his family “left ‘Special Settlement’ Ujma in the Pierwomajski Region, Arkhangelsk Oblast on Thursday 28 August 1941 bound for the city of Samarkand in the Uzbekistan Republic” (9) where Zachariasz and his eldest son Boleslaw would enlist in the newly forming Free Polish Army.

Generally, when the head of the house was notified of his successful enlistment in the newly forming Polish Army Corp, the women and children were basically assured of a place on the boats bound for the many Polish Displaced Persons’ Camps in northern Africa. The single men and women, together with youths (mostly 10 to 15 years of age) of almost fighting age – ‘boy soldiers’, or ‘Junaks’ ended-up in Palestine.

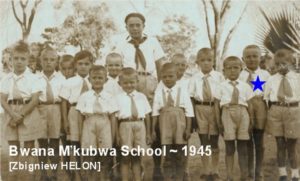

Elzbieta Misiura and her family ended-up in the Polish Displaced Persons’ Camp in Makindu, Kenya; Zbigniew Helon and his mother Genowefa found themselves in a Polish Displaced Persons’ Camp in Bwana M’Kubwa, Tanganyika – now Tanzania.

Token Recognition!

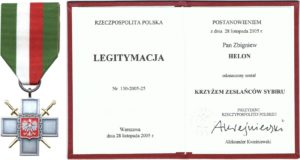

On Monday 28 November 2005 – after my Application to Polish Authorities – my parents Zbigniew and Elzbieta Helon (nee Misiura), were awarded the Polish Siberian Deportees Cross (Krzyżem Zesłańców Sybiru) by the then President of the Republic of Poland, Aleksander Kwaśniewski.

The Polish Siberian Deportees Cross was struck and issued to honor those of the Polish diaspora scattered around-the-world, whose calamity, plight, suffering, endurance and survival had gone totally unrecognized up until that time.

Of the Polish Siberian Deportees Cross my late father said: “Pfft! For all we lost and suffered; we were betrayed by the British, the Americans, the Jews, and our own government. We lost our properties, families, our country, and all they give us is a piece of ribbon and a lump of silver!” (1)

References:

(1) Helon, Zbigniew ‘Alan’: Personal Interview with son Wieslaw George Helon: Toowoomba; Wednesday 24 September 2003.

(2) According to Elzbieta (Elizabeth) Helon (nee Misiura) in 2003, her mother Helena Misiura (nee Rzadiniec) and other older Poles “referred to Jews as ‘Zydowsk Gangarina (Jews were like spreading gangrene rot)’ and Ukrainians were referred to as ‘Czarne Podniebienie (Black Palate)’ because they would denounce anyone, even lie, if it was to their advantage.”

(3) Petform of the Jewish Christian Name spelt Symcha or Szymcha; meaning ‘joy or rejoicing’; Polish Szymon.

(4) Gurjanow, Aleksander. Member of the Polish Committee of the ‘Memorial’ Society: Moscow; Personal Correspondence to Wieslaw George Helon; Wednesday 14 August 2002.

(5) Helon, George. Remembering the Forgotten Holocaust of February 10. The Chronicle: Toowoomba; Monday 10 February 2020.

(6) Rogucki, Professor Antoni. Born in Pawlow on Saturday 23 October 1920 and died on Thursday 10 May 2018 in Warsaw. Rogucki was a neighbour of Pawel and Karolina Helon; Personal Correspondence to Wieslaw George Helon: Warsaw; Friday 4 October 2002.

(7) Instytut Pamieci Narodowei. Indeks Represjonowanych Tom XIV: Deportowani w Obwodzie Archangielskim Czesc 3 – Alfabetyczny Wykaz 10,344 Obywateli Polskich Wywiezionych w 1940 Roku z Obwodu Lwowskiego. Osrodek KARTA: Warszawa; 2004; pps. 68, 73, 77, 304-305.

(8) Helon, George. The Forgotten Holocaust (Blog). Monday 1 February 2021. URL: https://georgehelon.com/the-forgotten-holocaust/ .

(9) Gurjanow, Aleksander. Member of the Polish Committee of the ‘Memorial’ Society: Moscow; Personal Correspondence to Wieslaw George Helon; Sunday 12 January 2003.

Connect with Me!

Copyright (C) George W. Helon: Australia; 2018-2025.

Now with SSL Certification for your Security!